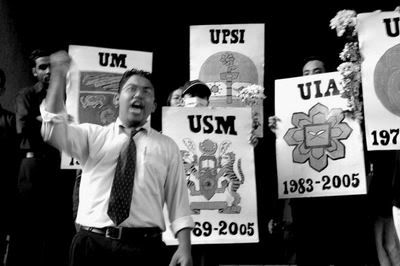

ADOPT AN ORPHAN FROM ACEH? NOT.Pictures and story by Ong Ju Lin in Banda Aceh

Looking for survivors.

Looking for survivors.It is a different world on the ground. For us working in the field, it is a world of mobile clinics, relief distribution, logistics, IDPs (internally displaced persons), UN coordination meetings, health surveillance meetings, etc…Ironically, while you’re at the place where the real stuff is and if you’re focused on one project, you can feel quite insulated from the news that is circulated outside of ground zero.

That was how I felt when I heard of Malaysian well-wishers who would like to adopt orphans after reading heart-rending news about children who lost their parents in the tsunami that hit northern Sumatra on a day after Christmas last year.

The subject of “adopting” orphans was raised by one Malaysian reporter working for a Japanese news station. He was with his two other colleagues when they ran into me and the Hospital Tentera KESDAM where our Mercy medical team was based. Expressing admiration for Mercy’s work, they gave us the thumbs up and said they were proud to be Malaysians.

One of them told me that with all the news about orphans, he knew at least five Malaysians who would like to be part of an “adopt-an-orphan” project and if we knew of such a programme would we notify him.

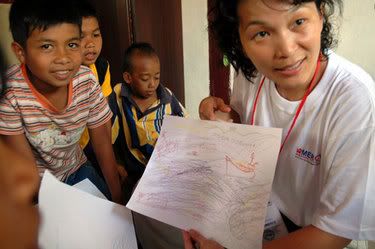

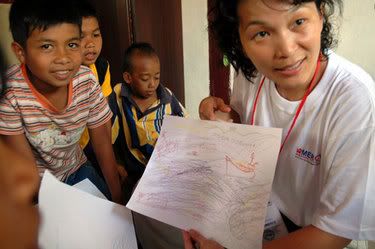

Orphaned survivors: alive and happy.

Orphaned survivors: alive and happy.I’ve seen those programmes. It gives the benefactor much satisfaction knowing that his or her money goes into raising an orphaned kid. In some programmes, the benefactor can choose a child from a photo album a child whose face calls out to him. Personally, I find that distasteful. It reminds me of men in priviledged position choosing post-mail brides from a less wealthier country.

I told our friend, the reporter, that there is no such programme here. Not that I know of. With 80% of Banda Aceh devastated, things were just starting to move, not to normality, but to move out of shock phase into relief response. I can’t imagine a project that demands such complex administrative effort in place.

And I was thinking of the orphanage we visited yesterday. The religious association that housed them was swamped with 200 children orphaned by the disaster. The

ustaz (religious teacher) used to run a

sekolah mengaji (school for learning to read the Quran) and suddenly found themselves with requests to take in orphans from surrounding villagers destroyed by the deluge.

All the kids have lost one or both parents. And yet, we would not have known their harrowing experience had we not probed. When asked by Mercy volunteer psychologist Loh Sit Fong to draw what was troubling them, many hauntingly depicted the same things.

The children's drawings depict their haunting memories.

The children's drawings depict their haunting memories.Giant waves bearing down on people, houses and trees; capsized boats, helicopters hovering above, and survivors escaping into the mountains. When asked if they were in the picture, they would point out to one of the stick figures running on the hills. According to our doctors, some of them complained of heart palpitations and insomnia. These are post-traumatic symptoms.

But we were amazed by their resilience. Loh said the kids told her that it was because everyone had the same experience that they could rationalize their own experience. They were not alone. It was indeed a fate of humanity, God’s will. “We thought it was

hari kiamat (Judgment Day),” they said. It was with this knowledge of collective suffering that they could find strength to let go the lost of their families, find solace with each other and camaraderie with the living.

At the orphanage, they were all treated equally, wearing old donated clothes, eating the same food, getting the same treatment from their teachers, praying at the same time and sleeping on the same plank beds. After the unimaginable chaos, the routine gives them a sense of security. They went wild when we gave each a balloon and a soft toy to play with. They were equal in suffering and equal in receiving love and care.

Praying together at set times gave them a sense of routine and stability.

Praying together at set times gave them a sense of routine and stability. Volunteer doctors say the orphans have post-traumatic symptoms such as insomnia.

Volunteer doctors say the orphans have post-traumatic symptoms such as insomnia.I can’t imagine an “adopt-a-child-programme” being in place here. How do you tell an orphan who has a sponsor that he or she is more deserving than the others? How do you tell the other children that they are less deserving or that they have to wait for sponsors before they could get their uniforms to go to school? Or if indeed if all 200 orphans each had a benefactor, how do you control what each benefactor sends to his adopted child?

What if the sponsor forgets about the kid after a year or a few months of sponsoring him? How do you explain this to the kid?

It would be an administrative nightmare to organize a one to one “adopt-an-orphan programme” here where the most basic communication infrastructure has been destroyed.

The Christian-based World Vision runs a sponsor-a-child programme. Each child costs USD$30 a month but sponsors are not told how much of it goes to administration and how much of it goes to the child. I was told half of it goes to the community and half goes to the kid eventhough the child is advertised as the receiver, picture, hobbies and all.

Yes, the children need help. The people who run orphanages need help too- to run it. If Malaysians care for orphans, then they should care too for the people closest to them - the people managing the orphanages. Many have lost family members too. Everyone in Aceh is affected one way or another by the disaster. I talked to a father who lost his entire family to the sea.

“We could not outrun the waves coming behind us. My wife was running in front of us with our youngest child, and I was holding my two children. When the waves hit, I could not hold on to them. I had to let go off my children.”

He thought he would drown under the fury of the waves, and he called out Allah’s name over and over. The third time he surfaced, he found himself hanging on to a roof. Everyone was gone.

I could not hold back my tears as he spoke with such equanimity and reverence to his own lost. “Betapanya kuasa Allah” (How very powerful God is)," he said.

When he saw my tears he said: “Child, do not cry.

Allah yang memberi, Allah yang mengambil.” (Allah gives and Allah takes away.)

Most Acheneses whom I spoke to are happy to tell me that they have connections to Malaysia. They are grateful that we have come to their aid. They have either worked or studied in Malaysia, have relations there, or have been arrested at Semenyih detention camp for being “illegal immigrants.”

One told me that because of our amnesty programme just before the new year’s crackdown on undocumented migrant workers, they have returned home bringing with them electronic items and other gifts for families, which unfortunately have all been lost in the earthquake and tsunami.

In Malaysia, an Achenese is an “illegal immigrant”. We do not recognise Achenese escaping from political unrest in the conflict-ridden province as political refugees. We detained them for months and sent them back to die, if they had not already died from treatable diseases in the notorious Semenyih detention camp.

Our hypocrisy makes me angry - that our xenophobic paranoia would not allow us to see them as brothers, but now we are queuing up to adopt their children.

And they are our brothers. We share the same types of foods, the same language, the same religion. We are the same people violently separated by an artificial boundary imposed by our colonial masters (the British in Malaya and the Dutch in Indonesia) for political and economic interest just less then a hundred years ago. But now our governments hang on to them as if it was God-given, as if we have been different people from eternity.

This outpouring of generosity… how genuine are we in being generous? Can we only respond to a forgotten people after a tragedy of this scale? Can we not see them as human beings equal to us? Can we only respond to them as unequals – hate and fear them (as illegal immigrants) or pity them (as victims of tsunami)?

Is pity the only emotion that can move us to help?

I believe it is because we do not see them as equals that we are talking about adopting their orphans as a way to save them. They do not deserve only our pity.

They are an independent and resilient people. Many are going back to rebuild their homes and lives because they could not just wait while their government decides what to do. They are tired of receiving hand-outs of old clothes and instant noodles. Already it seems like the small town of Lumbaro a little away from the devastated area - noisy and clogged with animals, people and traffic - has become the new centre.

I believe if we offer them a little head start - some capital and later, jobs- they would be able to rebuild their lives on their own, while the billions of aid concentrates on rebuilding infrastructure like roads, providing clean water and electricity. It is not pity they need, some help, yes, but respect and dignity as a people.

Ong Ju Lin was in Banda Aceh with Mercy Malaysia 2nd Mission from Jan 2, 2005 to Jan 15, 2005. The opinions expressed in this feature is entirely my own and do not represent that of Mercy Malaysia.